TW! Abandonment. Physical, Psychological and Sexual Violence. Self-harm. Death and Suicide. Drug Addiction.

“A Little Life” is quite a controversial book. It’s even been referred to as trauma porn.

If you don’t know what trauma porn is, you can check out this article. But, in short:

Trauma porn is media that showcases a group’s trauma not for the marginalised group's sake but to console or entertain the non-marginalised group.

Trauma porn makes consumers feel bad for the marginalised group and then feel good about themselves for being compassionate. And, satisfied with their compassion, they return to their everyday lives unchanged.

But that’s not really what this book did for me.

There’s quite a bit of heavy trauma depiction in this book. But the characters are too unrealistic and cartoonish for me to care about their fictional lives and struggles.

More than compassionate, I felt annoyed.

⭐️ Yet, this book has a rating of 4.33 on GoodReads, with 59% of ratings being five stars.

Even Dua Lipa loved the book.

As a devoted and lifelong reader, I will happily admit that more than a few books have made me cry. But Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life is different: it was one of the first books I openly sobbed after reading. By the end of it, I felt profoundly changed. I’m not exaggerating when I say this novel challenged everything I thought I knew about love and friendship. It’s one of those books that stays with you forever.

Although not as much, I enjoyed it, too. And for that, I think it’s worth sharing – and criticising.

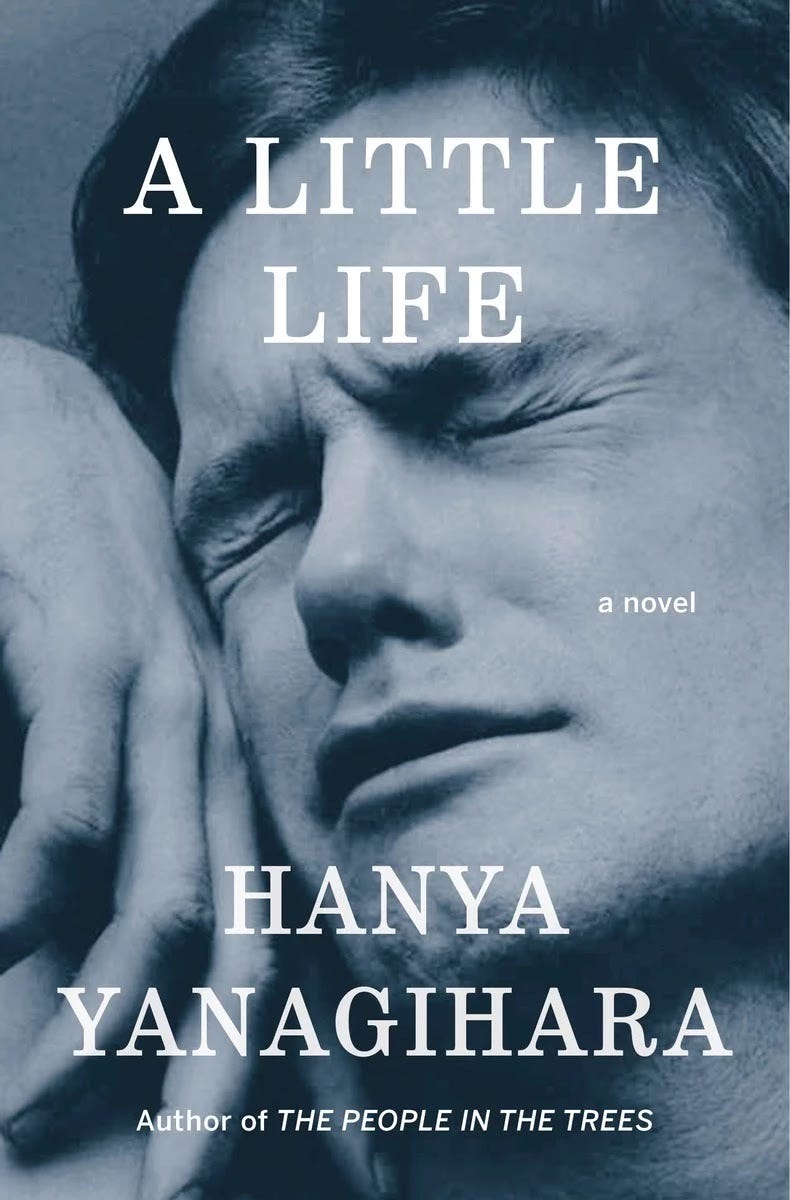

What’s “A Little Life” about?

“A Little Life” follows four college friends – Willem, Jude, JB, and Malcolm – who are in their late twenties and early thirties and live in New York City after graduating from a prestigious university in Massachusetts to establish their careers.

Willem is an aspiring actor, Jude is a litigator, JB is a painter, and Malcolm is an architect.

But that’s not really what the novel is about. It focuses on their friendship and past, particularly on Jude, who is brilliant, mysterious and, above all, traumatised.

Jude’s traumatic childhood – and life

[This is a lengthy and explicit summary of the 750-page novel. Feel free to skip to ‘Hanya Yanagihara’]

Jude was abandoned as a baby and left at a monastery.

I imagine growing up in a monastery would entail strict daily routines involving prayer, meditation, and religious services. I imagine religious education would be essential, and everyone would be expected to participate in communal chores.

I imagine growing up in a monastery would mean you have no toys and instead live an austere life. I can’t imagine what the fun activities might be. But I imagine there is limited contact with the outside world.

Jude’s experience was a bit more intense than that.

He was regularly beaten and sexually abused by the monks, who were supposed to care for him. The isolation of the monastery enabled the monks to exploit Jude for a long time without fear of outside interventions.

But when Jude turned eight, Brother Luke, the only monk at the monastery Jude trusts, took him away from the abusive environment.

But don’t get excited; he didn’t rescue and provide him with safety. Instead, he chose to continue to exploit him sexually.

They travelled together for a long time with few possessions. It’s probably challenging to earn money on the road. And you surely need money on the road. But who would subject an eight-year-old to prostitution for any reason whatsoever?

Luke. He would, and he did.

One of the most messed-up things about this is that Jude still trusted him. Luke made him believe that he loved him and cared for him. He made him think that no one else would ever care for him. He turned the abuse into something Jude was grateful for.

Despite having left the monastery, Jude was still isolated with his abuser. He trusted and depended on him. You can imagine what this did to Jude’s understanding of relationships and self-worth. And don’t worry, we’ll get to it in a bit.

First, I must let you know this didn’t go on forever. At some point, Jude realises the truth and escapes from Brother Luke, only to encounter other sick men who also abuse him. Jude is vulnerable and ridiculously unlucky, and he continues to be physically, psychologically and sexually abused, one sick man at a time.

Jude seeks help repeatedly, but he’s always blamed or victimised in a condescending, unhelpful way – or abused again. Society – am I right?

Eventually, Jude escapes the cycle of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse when he gets hit by a car at the age of fifteen.

Jude is then hospitalised and undergoes many medical procedures and physical therapy on his legs. But the pain never goes away, and he’s never able to walk without a cane again. Unsurprisingly, he deteriorated his self-esteem and inflated his sense of brokenness.

His chronic pain and walking difficulties not only made him feel inadequate and helpless. They also served as a reminder of the years of abuse he endured, his escape, and how that didn’t turn out as he’d hoped.

Why did his cycle of increasing suffering only end with a new cycle of suffering – again? We didn’t need more trauma porn. And I didn’t need any more hope drained out of my soul.

Jude’s history is visceral, but my summary isn’t comparable to the detailed, graphic narrative that extends beyond 700 pages.

Unfortunately, in the book, despite the extensive telling of his traumas, we don’t get to know much about Jude and how he experiences the traumatic situations. As I said, it’s just trauma porn. We only get to know, in detail, that they happen and that Jude will never have a normal life because of that.

What about the others?

At some point, Willem’s acting career starts to take off, Malcolm becomes a successful architect, and Jude becomes a successful lawyer. JB wasn’t as lucky. While everyone else achieves their goals, JB struggles with cocaine addiction.

But JB is not Jude, so we don’t care that his career took off and then declined as he struggled to maintain his artistic integrity while achieving commercial success.

We only care about how his cocaine addiction affected his relationship with Jude and that he envies Jude.

And, honestly, who wouldn’t envy Jude? Or, at the very least, admire him?

Jude’s relationships are far from perfect, but he always has the support of his friends – who will always choose him over JB; his adoptive father – who legally adopted him in his mid-twenties; his therapist – who sucks but always picks up the phone; his orthopaedic-surgeon friend – who for some reason makes time for him any time of the day any day of the week to give him sutures or other care after severe self-harm or suicide attempts but never sends a referral; and his social worker – who does her best.

Jude is also a successful corporate lawyer, although he’s not passionate about the law. We’ve never seen him work; we’ve just heard others say he is outstanding. And I honestly wonder how he succeeded. He can’t keep a stable relationship, not even with himself, yet he is the most outwardly put-together human I know of, fictional or not. Oh, and he also sings like an angel. And he plays the piano equally well.

He’s good at more things, but you get the point.

Willem, Jude, JB and Malcolm are close friends. But, like in any friend group, there are friend sub-groups. Willem became Jude’s confidant and primary support system.

‘Who is Willem?’ you may ask. We don’t know, but he’s not Jude, so we don’t care.

Jude struggles with his identity and self-worth and struggles to find joy and fulfilment in life. But he eventually starts a romantic relationship with Willem. This after he dated Caleb, whom I forgot to mention. But all you need to know is that he sucked.

Jude is happy with Willem, but he is still haunted by his traumas, which, of course, affect their relationship. Jude’s trust issues lead to pretty mundane and uninteresting challenges that are to be expected from a no-trust relationship.

But don’t worry, it doesn’t end there. Willem, along with Malcolm and Malcolm’s girlfriend, dies in a car accident. And yes, you guessed it, Jude’s mental and physical health go to hell – or, well, deeper into hell.

Who is Malcolm? Oh, we don’t know, and we don’t care.

Luckily, he gets support from Harold, his adoptive father. His friend, the only other in the group still alive, JB, the cocaine addict, is also there for him. Andy, his therapist; Ana, his social worker; and Traylor, his surgeon friend, are also there for him.

But their help wasn’t enough. Jude takes his own life.

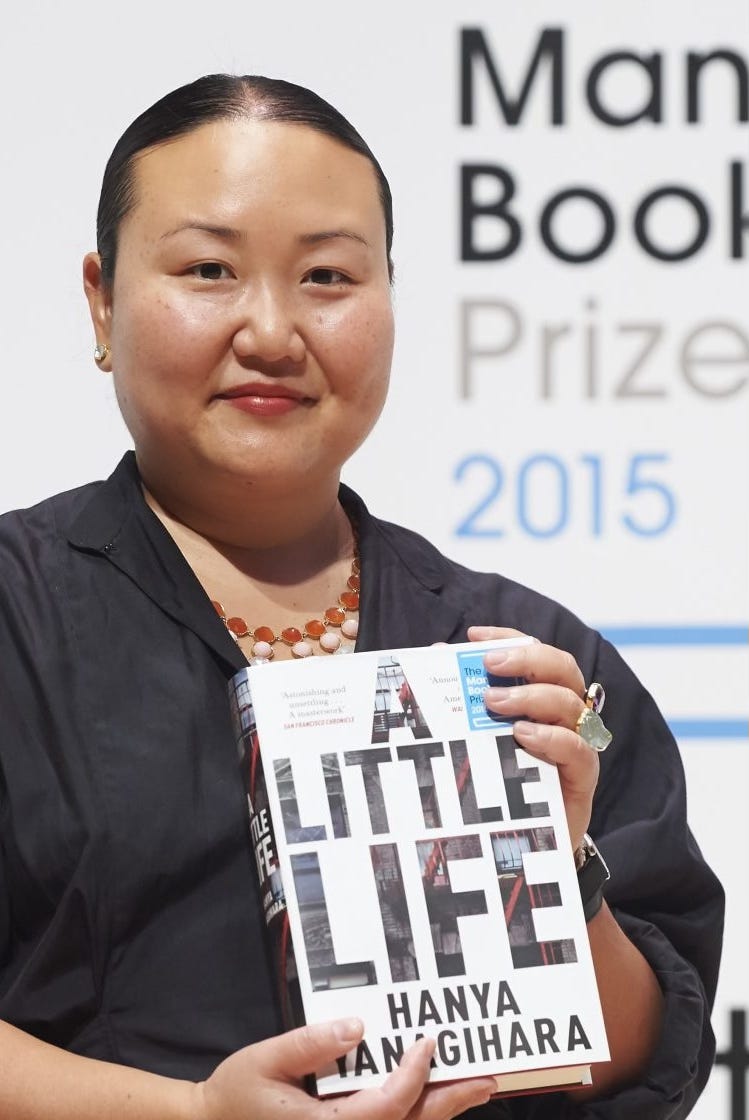

Hanya Yanagihara

This book has been criticised for many more things than mentioned here. For example, the only black character, JB, of Haitian descent, is a drug addict; none of the queer characters have strong, determined queer identities, and they all have abusive relationships; the plot and character development often made no sense, and the writing felt ridiculously lazy; the story takes place over a few decades, but somehow, everything seemed to happen in 2014; all the thirty-year-olds in this book speak like they are fifteen – not only when they are thirty, but throughout the whole book, from childhood to the day they die; etc.

The play adaptation and the film of the play seem to have escaped this criticism.

But Hanya Yanagihara has also received her own, personal bit of criticism.

One reason is that she doesn’t believe in trigger warnings as an opportunity to opt out of reading her book.

To try to preemptively shield yourself from an experience – to say, in essence, this book is about something that I fear is going to really upset me, so I’d better protect myself by not exposing myself to it at all is not only limiting, but also means you might be preventing yourself from experiencing something else, something you thought you never would, or never have.

It’s unclear whether she believes we should have trigger warnings or not. But she certainly, as she’s stated multiple times, doesn’t think they should stop you from reading a book.

I agree – to a very small extent. But I think this shows her complete lack of understanding – or disregard – of mental health and the mind in general. She has admitted to doing little to no research before writing ‘A Little Life,’ which sadly shows.

To say that one has to experience triggering situations for the sake of experiencing things is insensitive, to say the least.

But, more controversial has been the reason she chose suicide as Jude’s escape.

[T]herapy, like any medical treatment, is finite in its ability to save and correct. […] I don’t believe in [ talk therapy] myself. One of the things that makes me most suspicious about the field is its insistence that life is always the answer. Every other medical speciality devoted to the care of the seriously ill recognises that at some point, the doctor’s job is to help the patient die; that there are points at which death is preferable to life. […] But psychology, and psychiatry, insists that life is the meaning of life, so to speak; that if one can’t be repaired, one can at least find a way to stay alive, to keep growing older.

I find this statement difficult to disagree with. I am not ‘suspicious about the field,’ but I wonder whether we should force people to live lives they don’t want to live.

I believe we should protect the lives of those who want their lives protected and those who can’t decide. I believe treatment can change someone’s mind and help them live happy lives. But I also believe we have the right to die as much as we have the right to live.

This reminded me of the scene from The Incredibles in which Mr. Incredible is sued by Oliver Sansweet for saving him when he jumps off a building.

Lastly, I’m intrigued by how she often reduces psychology and psychiatry to talk therapy. But I guess her point remains the same.